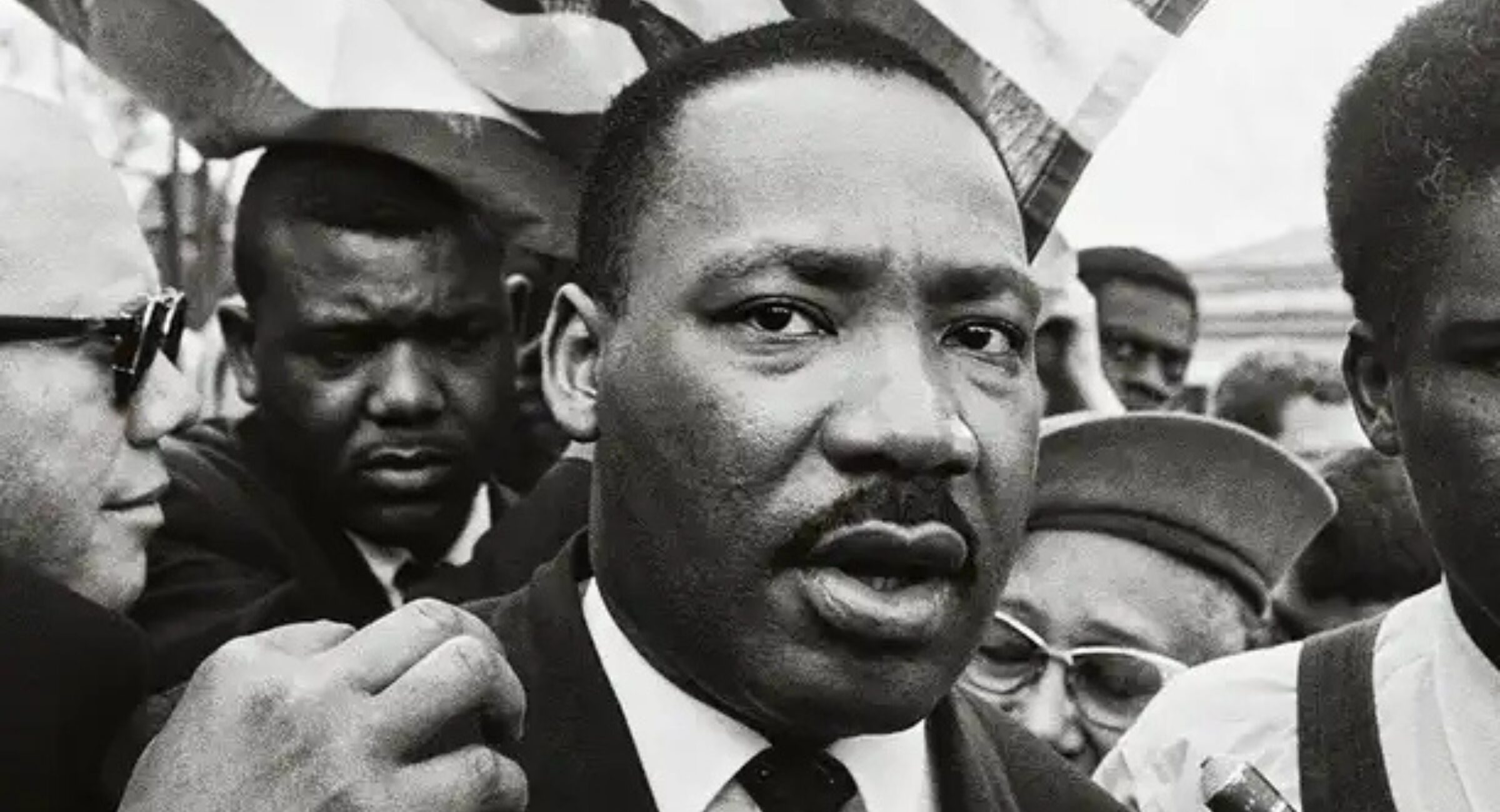

On this Martin Luther King Day, we give thanks for the life and work of this American hero and reflect on ways his work can and should inform our own. For organizations advancing the cause of justice, King’s example remains instructive.

Dr. King framed his arguments in terms of the larger American experiment in democracy. He elevated the voices of people most affected by the problems he sought to address. He was willing to work with anyone to achieve his goals—a reflection of his awareness that people are imperfect and his faith that we are all created in the image of God. And he advanced a vision of freedom that was both legal and substantive, recognizing people’s need for work and well-being.

Keep reading to learn more.

Freedom is the Goal

In April of 1963, sitting in a jail cell and using scraps of paper and a pad left by his attorneys, Dr. King penned “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” The letter is today considered an essential piece of American political thought and a classic of nonviolent resistance. He wrote it in response to fellow clergy who opposed his methods of direct action and civil disobedience. He took particular exception with the public figure “who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom.”

Though writing from a jail cell, he nonetheless expressed confidence, rooted in his faith, that the cause of freedom would prevail. “We will reach the goal of freedom in Birmingham and all over the nation,” he wrote, “because the goal of America is freedom.”

This is a thought worth lingering on: The goal of America is freedom.

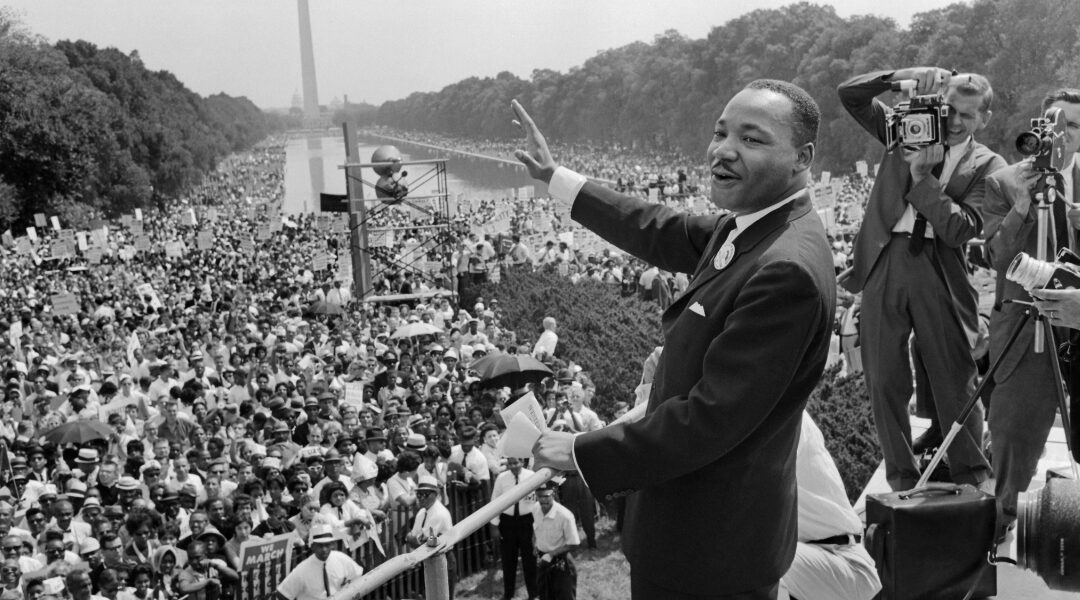

It’s a theme that King returned to throughout his public life. In his most famous address, the “I Have a Dream” speech, King called the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence a “promissory note to which every American was to fall heir” — a note that promised that all Americans “would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The problem for King, then, was that the country had too often defaulted on its promise. That promissory note too often amounted to a “bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

“But,” he continued, “we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.”

This is key to understanding King’s approach to effecting change. He drew from the language of the American founding. He expressed faith in the country’s ability to move forward. And he offered his cause—the cause of freedom—as the fulfillment of the country’s promise.

Here at REFORM, we honor King’s legacy through a relentless focus on freedom, recognizing that a system that can send a mother back to prison for crossing state lines or missing a meeting with a probation officer is not a system that promotes true freedom for all.

King’s Vision of Freedom

Dr. King’s understanding of freedom was deep, nuanced, and complex.

Through his organizing and moral witness, he helped set the stage for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which officially ended legal discrimination in employment and public accommodations in the United States. Just a year later, he helped achieve passage of the Voting Rights Act, which banned poll tests and literacy requirements that had been used to disenfranchise Black voters.

But King’s conception of freedom went beyond legal protections against discrimination. Freedom meant more than being free from oppressive practices; it also meant freedom to build lives of meaning and dignity. In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, he said, “I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality and freedom for their spirits.”

For King, then, freedom was about community, belonging, safety, and having access to the basic necessities of life. Freedom was the recognition of human interdependence, the conviction that all people are “part of an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

How can advocacy organizations incorporate this vision into their work?

A place to start is to recognize that people closest to the problem are often closest to the solution—a principle we take seriously here at REFORM, ensuring that people who know America’s supervision system firsthand play a key role in our policies and campaigns. If we’re all in this together, then we’re all in this together. And we need to hear from everyone, not just those who traditionally have access to power.

At REFORM, we also strive to live up to King’s ideal of freedom in how we think about transforming supervision systems. When people leave prison or jail, they need concrete support and tangible reminders that they are part of the “single garment” King describes: jobs, housing, health care, and a beloved community that lifts them up.

King’s Commitment to Building Coalitions

When it came to effecting social and political change, King was a clear-eyed realist. A student of the philosophy of the Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, he didn’t think societal transformation would come about through moral argument and persuasion alone; he recognized the need for building power.

That’s why you’ll find photos of King with political figures as ideologically diverse as Richard Nixon, Dwight Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson, and Robert Kennedy. He understood the need to talk to—and find ways to work with—everybody.

King understood that creating change sometimes requires that you find common ground with people with whom you might not otherwise agree. Central to his vision was the belief that all people are in some ways flawed, limited in their ability to know the full truth. Given this, we have to find and seize opportunities to make the world a little more just. But his willingness to engage in the messy reality of politics and the nuance of policy did not compromise his moral clarity. When hard truths had to be told, he told them.

Today, ninety-seven years since King’s birth and fifty-eight years since his tragic death, his example still calls us to our best selves and highest ideals. Freedom remains the goal, and the work of achieving it requires that we understand what real freedom means and embrace willing partners in achieving it.