Andre Cooper can hardly believe it. After ten long years, his time on probation is almost coming to an end.

“Man, I feel like I can go to the moon right now,” says the 43-year-old Roanoke, Virginia resident.

It has been a long road for Andre, one that began when he was young and his mother lost custody of his two younger sisters. From there, challenges in the household sent Andre down the wrong path.

“That’s when I turned to the street life,” he says. Trouble soon followed, and not long after, so did a prison term. Andre successfully served his time; after he got out, he was put on probation for a decade.

Looking back, he recognizes that he had many interests and talents as a young man that weren’t nurtured; he fared well in academics and was drawn to sports and other community activities. But, he says, another side–what he calls “a toxic side”–gained the upper hand. He had seen many men in his family go down this same path, some serving decades in prison.

While incarcerated, Andre vowed to break the cycle. He promised himself that he’d be the last member of his family that the system swallowed whole. While serving his time, he earned his GED and started earning college credits. He read voraciously. He even learned AutoCAD, a computer design software application, and took graphic design classes offered inside.

When he returned home on probation in August 2015, he felt ready to hit the ground running. “I have a lot of talents,” he says, “and I wanted to put those things to work to rebuild my community.”

But probation proved to be a cycle of anxiety and uncertainty. The system didn’t offer him resources or support; instead, he says, it treated him “like that same old criminal.”

No matter how much progress he made–returning to community college, building a graphic design business, voluntarily attending mental health and substance abuse treatment–he felt as though his probation officers saw him as little more than a risk to be managed. Where encouragement would have gone a long way, Andre was instead met with skepticism: “I felt that I wasn’t being taken seriously in the positive things that I wanted to accomplish in my own life.”

Andre Cooper is one of 53,000 people in Virginia’s probation system – the largest segment of the Commonwealth’s criminal justice system and one that frontline law enforcement officers say is struggling under the weight of overburdened probation caseloads and chronic understaffing.

Andre felt this firsthand, switching probation officers with astonishing frequency. By the time he’d built a rapport with one, he’d be forced to work with another. And, amid all this change and confusion, he lost his mother to an overdose. The loss led to a wave of depression; he even worried he might relapse. He put himself into treatment and found a way to remove himself from negative influences, ultimately moving to Roanoke to build a better life.

Financial pressures compounded his challenges. Lucrative job offers out of state were off the table because the terms of his probation required him to stay in Virginia. To make ends meet, he worked two or three jobs–and still managed to find time for treatment programs, meetings with his probation officer, college courses, and other appointments that required him to commute across town. Meanwhile, he was expected to pay fees to the court.

“I was jumping through hoop after hoop,” he says.

Still, he pressed on. He honed his natural gifts–talents for art and cooking, especially. He took odd jobs. He kept up his exploration, begun while incarcerated, of life’s most pressing questions. Who are we, deep down? What are we called to do in the short time we’re here?

A probation system designed to help people thrive and keep communities safe would have recognized Cooper’s strengths and helped him build upon them. But instead, the system made Cooper feel as constricted as ever–not only by the rules imposed on him but also by the stigma that seemed to follow him like a shadow.

These challenges tested him, but they didn’t break him. He dug deep and remembered those questions he had put to himself long ago. Who is Andre Cooper? A man who is more than his circumstances–a man determined to do some good with the life he’s been given.

“Looking back at it,” Cooper says. “I can’t say probation brought out the best of me, but it made me look at the best within me. It made me harness my own self-talents and bring more out of myself… I would say it was worth it.”

Today, as Cooper approaches the end of his 10-year probation term, he remains steadfast in his desire to apply everything he’s learned to make his community stronger and safer. He dreams of starting a mutual support group among other formerly incarcerated men to offer guidance about business, entrepreneurship, cooking, you name it. “I want to show people how we can help each other,” he says.

And he’s lifting his voice in support of probation incentives legislation HB 2252 and SB 936, which would allow people on probation to earn shorter terms for improving their lives through work, education, treatment, health insurance, and housing. The bills recently passed the General Assembly with a supermajority in the House and unanimously in the Senate. They now await Governor Youngkin’s signature. The legislation is consistent with Cooper’s views about how probation can best support success: playing to people’s strengths instead of simply waiting for them to fail.

Had these bills been in place, it’s possible that Cooper would have been off supervision long ago. He now hopes that creating a better probation system will be part of his legacy.

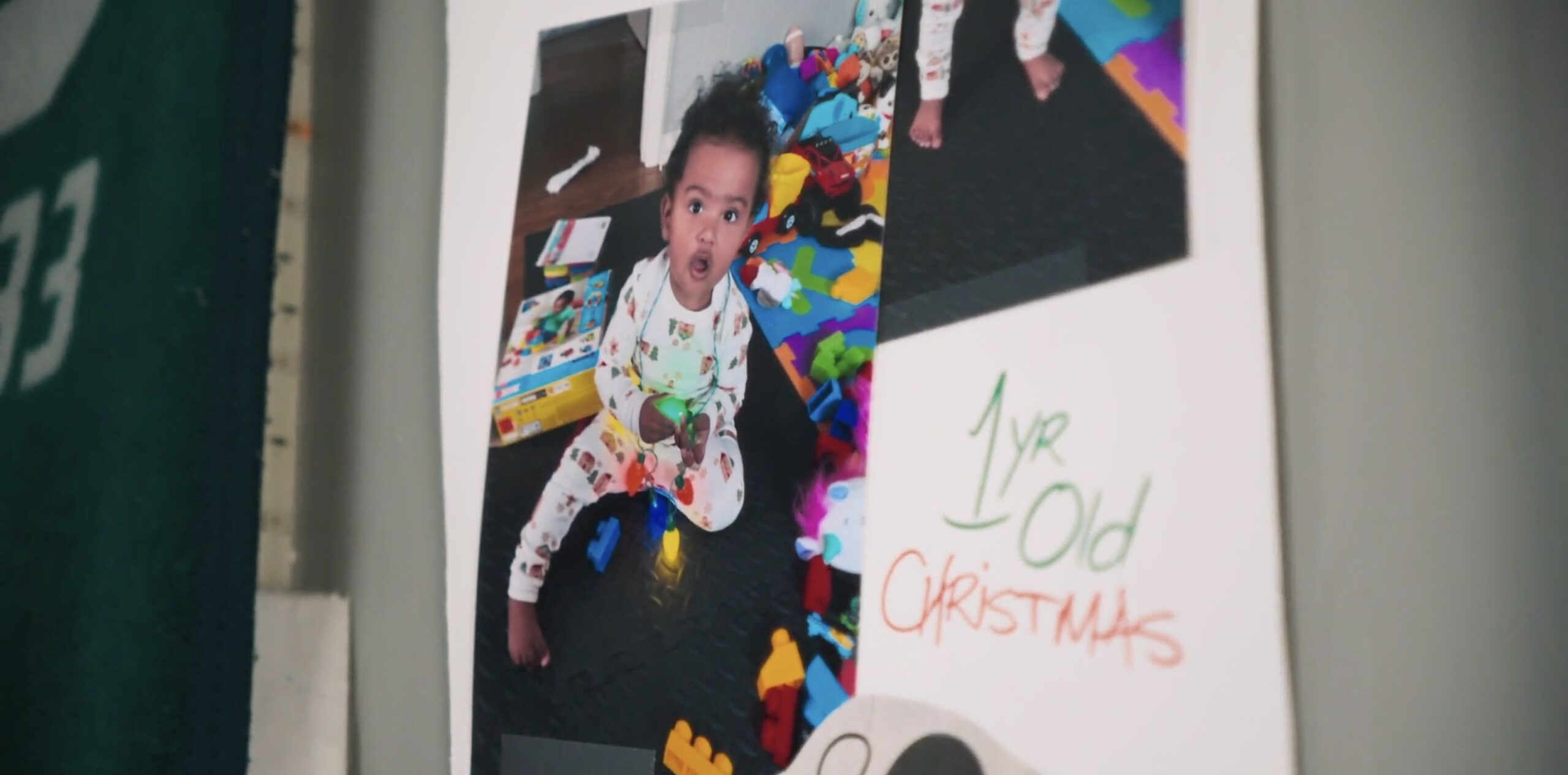

He’s also looking ahead. Cooper’s son Assan was born in December of 2023, an experience that clarified his life’s purpose in a way nothing else had. “It’s an exciting journey being a dad, I’ll tell you that,” he says with a smile. It’s as though he’s surprised by his good fortune–to have a real chance to break the cycle and raise this child in a world that has a place for him. “I plan to build an empire for this son of mine.”

Learn more about the Virginia Safety Coalition, a diverse, bipartisan coalition of leaders, experts, impacted individuals, and advocacy organizations committed to improving public safety, decreasing recidivism, and improving Virginia’s probation system.